The Gryphon In Art

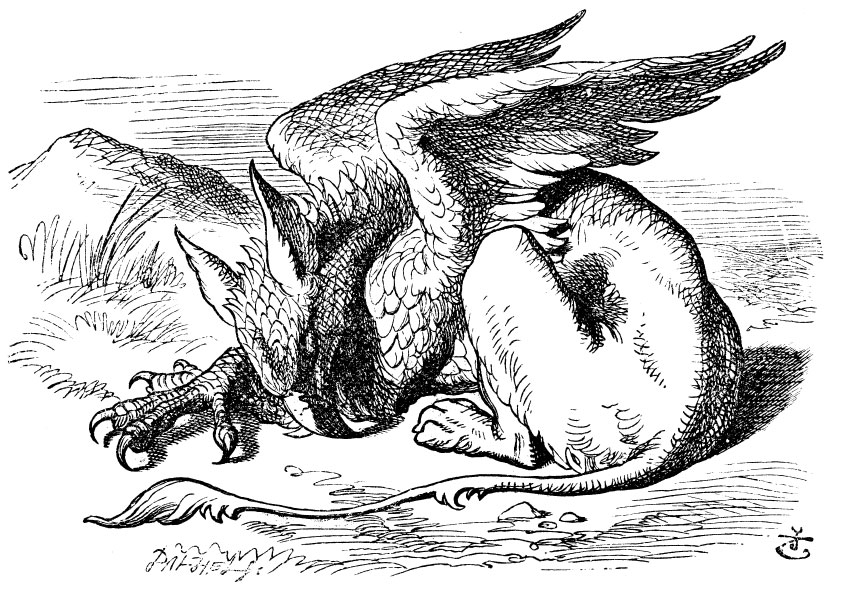

Illustration from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll, 1865. Illustration by John Tenniel. |

|

In Lewis Carroll's masterpiece, Alice's Adventures In Wonderland, the Queen brings Alice to meet a Gryphon asleep in the sun, then Carroll writes, "If you don't know what a gryphon is, look at the picture." What the reader of the first edition sees is one of the best known Gryphon pictures, seen to the left, drawn by John Tenniel. And so it has been throughout the centuries; the largely illiterate populace of the ancient world who could not read the description of a Gryphon by Ctesias, Pausanias, Aelian, et. al. are shown portrayals of the beast on vases, tombs, statues, seals and jewelry. If you are interested in how Gryphons are shown in today's media, then go to my Gryphon In Modern Media page.  Susa gryphon, ca 3000 BC. |

Pectoral of Mereret, Egyptian, Middle Kingdom, 12th Dynasty (1878-1841 BC) |

|

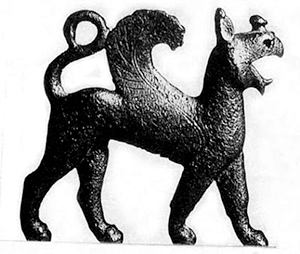

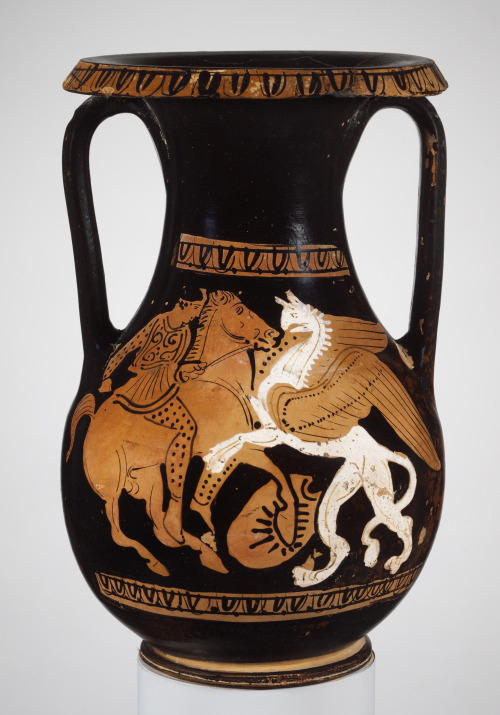

The Pectoral of Mereret catches the unique trait of the early Egyptian portrayal of the beast, the hawk head (sometimes that of a falcon). To the ancient Egyptians, the hawk was a most honored bird, and closely associated with the Sun, which would make it a natural choice to associate with the Gryphon. Late Egyptian art represented the Gryphon with an eagle head however. As early as 2,000 BC Gryphons were depicted on Egyptian tombs, and by 1,600 BC they wore the Atef, or White Crown, of Osiris, making the Gryphon the champion of Pharaoh and the guardian of the Egyptian kingdom. Later on, after influencing and being influenced by Hittite and Middle Eastern art, the Egyptian Gryphon obtained not only an eagle's head, but also loose curls flowing down it's neck.  Cauldron fitting of a gryphon's head, ca 700-650 BC.  Gryphon statue, ca 7th century BC. In Minoan Crete the Gryphon still served as protector and guardian, but seems to have achieved a more ornamental body. The curls described above went further down the Gryphon's back, ending at the base of the wings, if it was depicted with them. In the Palace of Minos at Knossos, a possible source of the mythic Labyrinth, colorful wingless Gryphons are presented not only on a fresco in the Throne Room, but also on a doorway to a shrine, and another fresco frieze. It is thought that Gryphons were somehow connected to the Minoan goddess (Magna Mater), since there are also depictions of priests leading Gryphons, of Gryphons pulling goddess' in a chariot, and of Gryphons guarding a goddess. The Gryphon appeared in all facets of Greek and Roman art and from time to time was portrayed with a conical knob on it's head as in the brass statuette to the left and the cauldron ornament to the right. The Greeks also had a tendency to curve the wings upward, as in left. A Greek bowl depicting two protective Gryphons, c. 500 BC Gryphons were common sights on vases, plates, bowls, relieves, etc., usually in the act of pulling a chariot, attacking an animal (mostly horses and stags), or serving as a protector, as in the bowl (c. 500 BC) to the right. Actually, the earliest example of "gryphomachy", or Gryphons attacking men, was on the back of a Greek mirror dated back to c.575-550. It was the stylized Gryphons on the helmet of a statue of the goddess Athena in the Parthenon which reminded Pausanias of Aristeas's poem, The Arimaspia. |

Terracotta pelike (jar), Attic terracotta, ca 465 BC. |

|

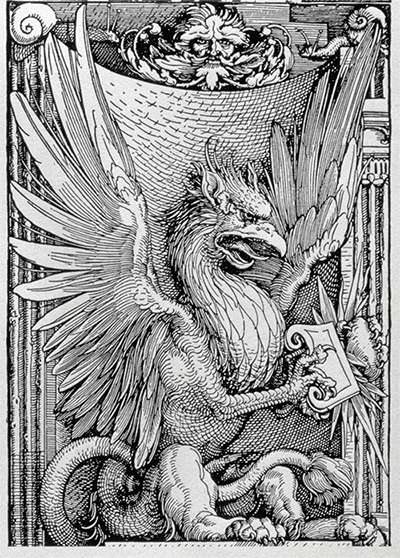

As the Gryphon is connected to the Sun/wheel/circle, it was also commonly depicted on coins.  Coins, clockwise from top left:  Woodcut of a gryphon, unknown artist, ca 1100.  The Triumphal Arch of Emperor Maximilian I, Albrecht Durer, ca 1459-1519. (cropped) Later on in medieval bestiaries, where it was still thought of as a real animal, the Gryphon had a very distinct form. Oftentimes in the bestiaries Gryphons were pictured as devouring some kind of animal, usually an ox or a horse, to promote the creature as wild and beast-like, therefore "evil." The stance in the woodcarving to the left, called passant in heraldry, was common for many animals in bestiary pictures, as are the spread (displayed) wings. Another common attribute is the tongue protruding from the mouth, and it is also seen to the left. (The extended tongue and spread wings were actually widespread even before bestiaries were made, as you can see from the Gryphon designs on the statues, coins and vase above.) A more elaborate Gryphon is shown to the right, but notice still the extended tongue and the spread out wings. It should be noted again that in nearly all instances where gryphons were portrayed in art, they were depicted as very real creatures, with no more magical or unnatural abilities than any other natural creature of the world. The art of history has kept this noble and natural image of gryphons alive and well today. |

© 2019 James Spaid. All rights reserved.